Craft, Advocacy & Legacy

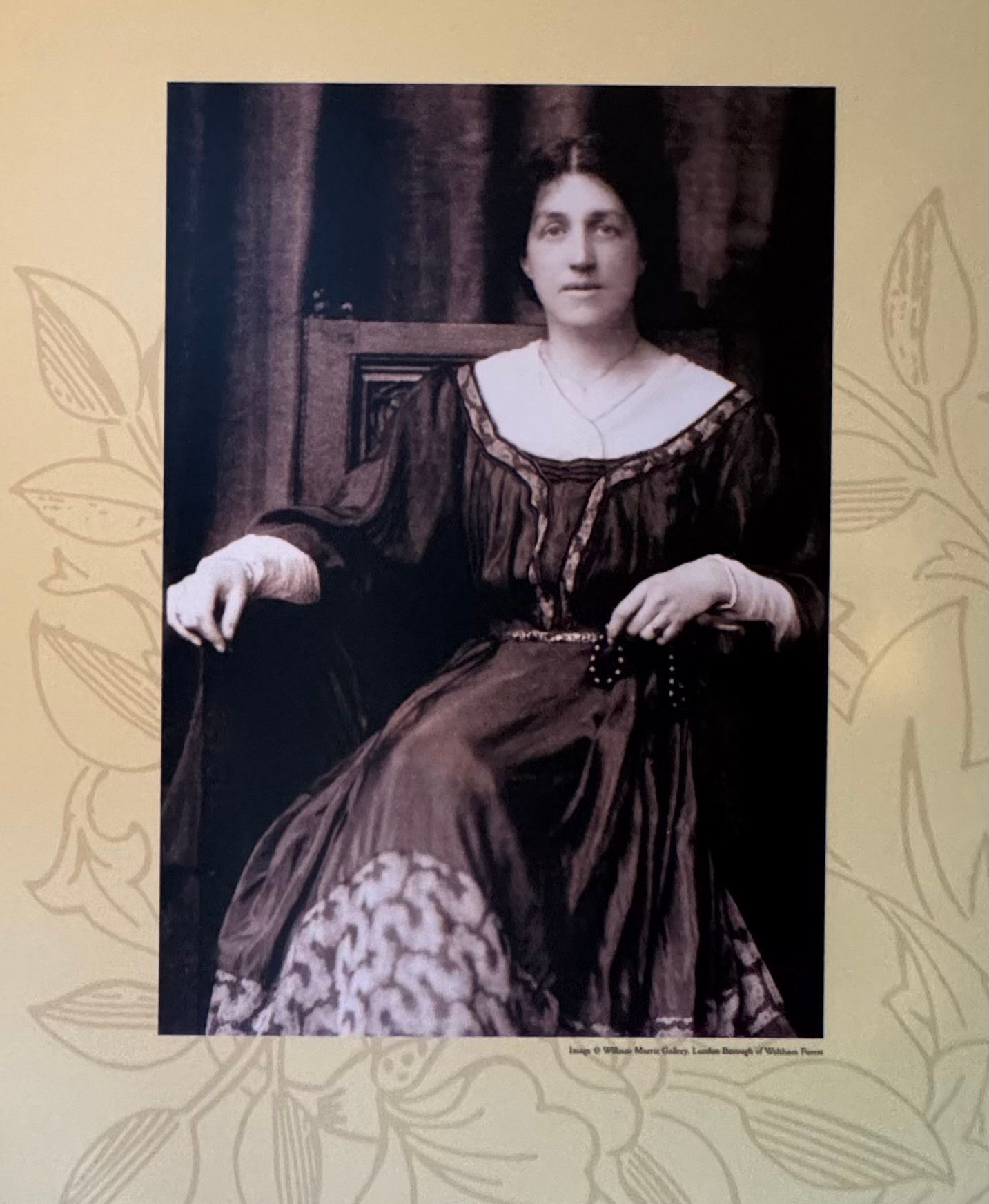

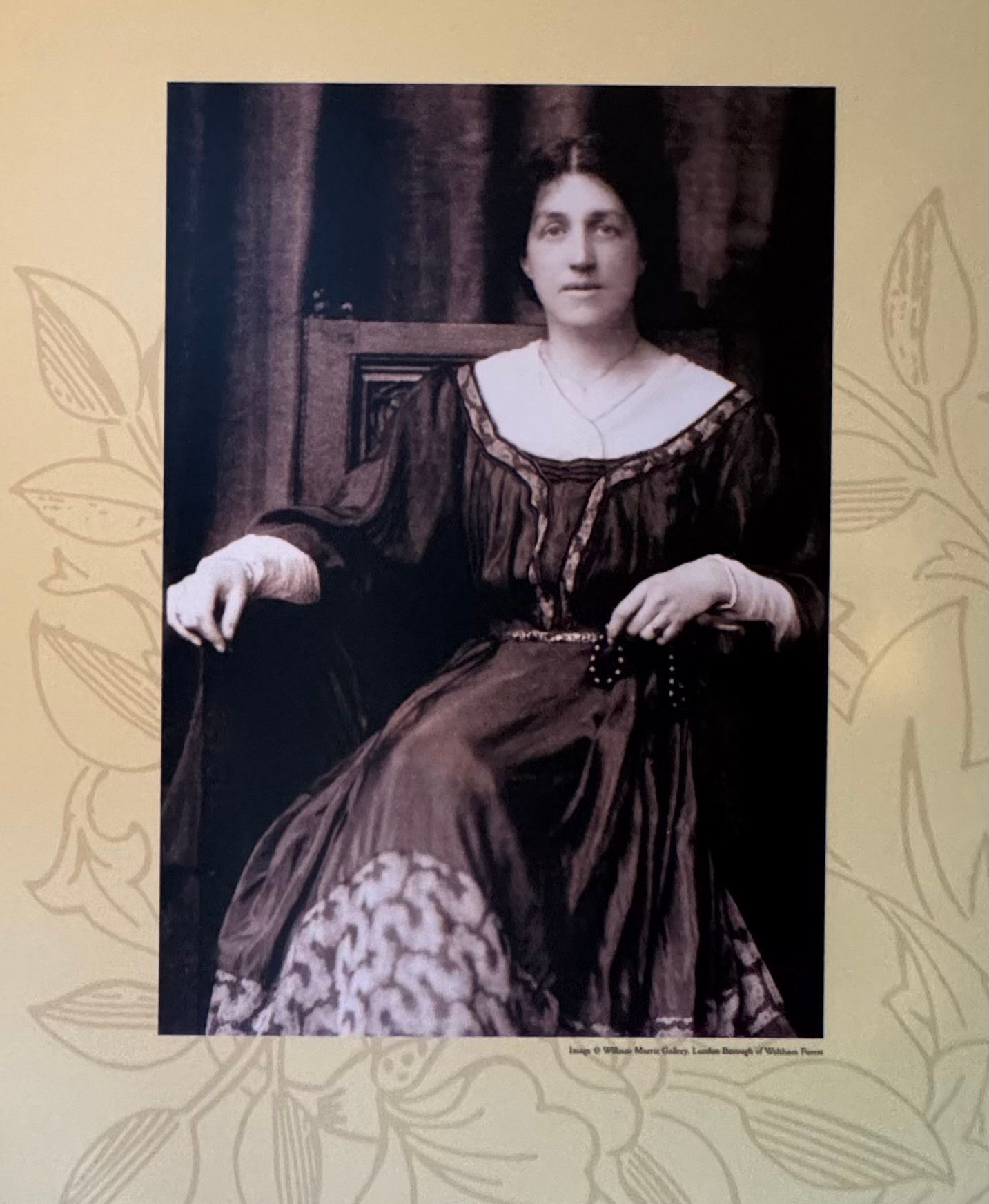

At just 23, May was appointed Manageress of the Embroidery Department at Morris & Co. in 1885, an extraordinary achievement in a movement largely dominated by men. Her responsibilities included overseeing design, coordinating embroidered work, supervising workers, liaising with clients and pricing commissions. Many of her designs were, however, historically misattributed to her father or to the house style, a common issue for women in collaborative or workshop settings.

Her embroidery style is notable for its balance between naturalism and stylisation: floral motifs, organic lines and a restrained palette. She authored “Decorative Needlework” in 1893, a treatise that aimed to elevate embroidery from a domestic pastime to an art form, arguing for expressive design rather than frivolous ornament.

After her father’s death in 1896, May relinquished day-to-day management of the embroidery studio, shifting her energies to her own design work, teaching, lectures and historic scholarship.

Personal Life

May’s married political activist Henry Halliday Spalding, but their marriage only lasted four years. She was involved in a chaotic affair with playwright George Bernard Shaw. By 1898, May had secured a divorce and ended her affair. She resumed using her maiden name and never remarried or had children.

In the late 1910s, May developed a close relationship with Mary Lobb, a gardener at Kelmscott Manor, the Morris family's Cotswold home. In her will, she left Mary more than £12,000 (almost £1 million today) and the lifetime tenure of Kelmscott Manor.

Slide title

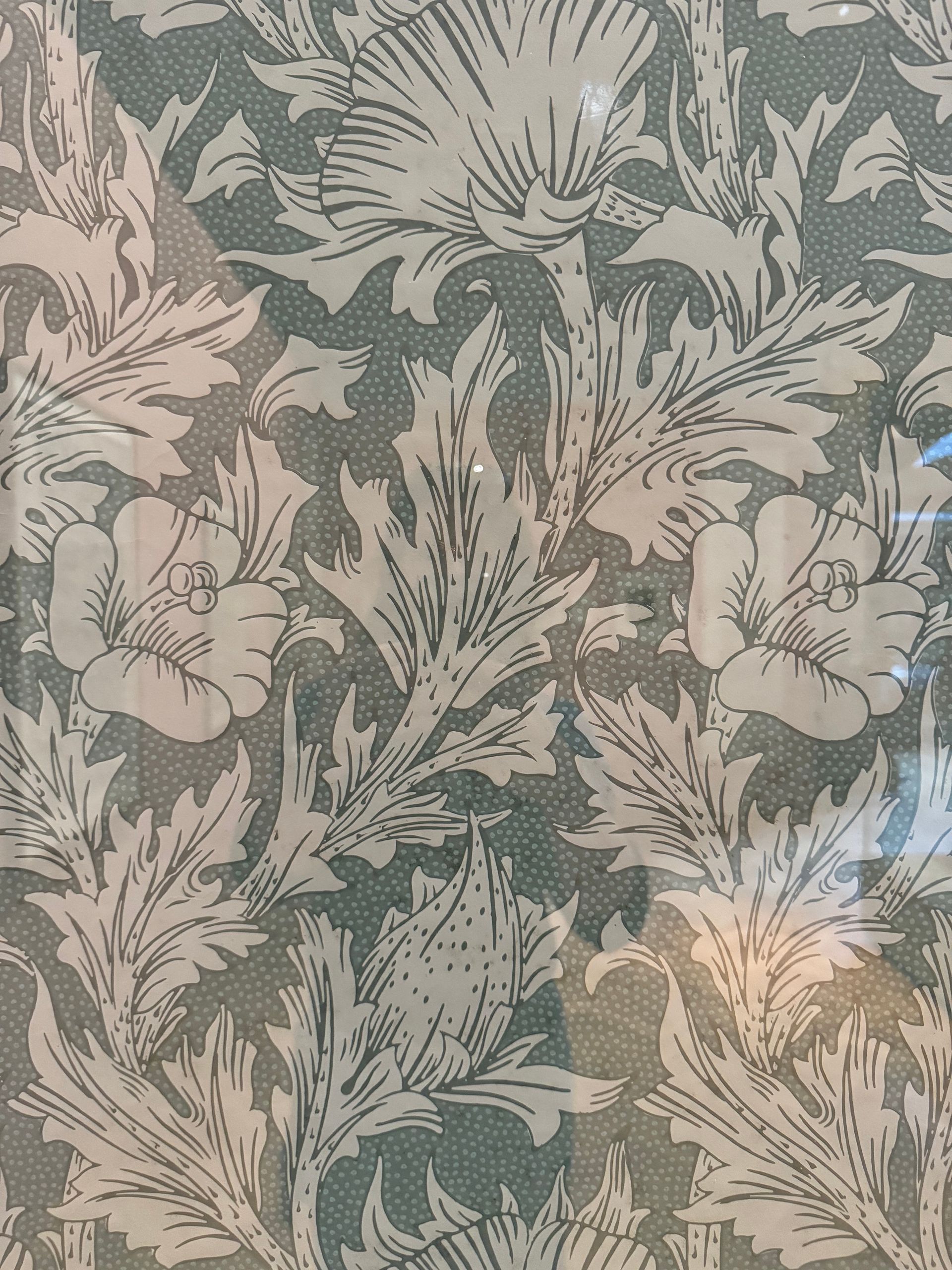

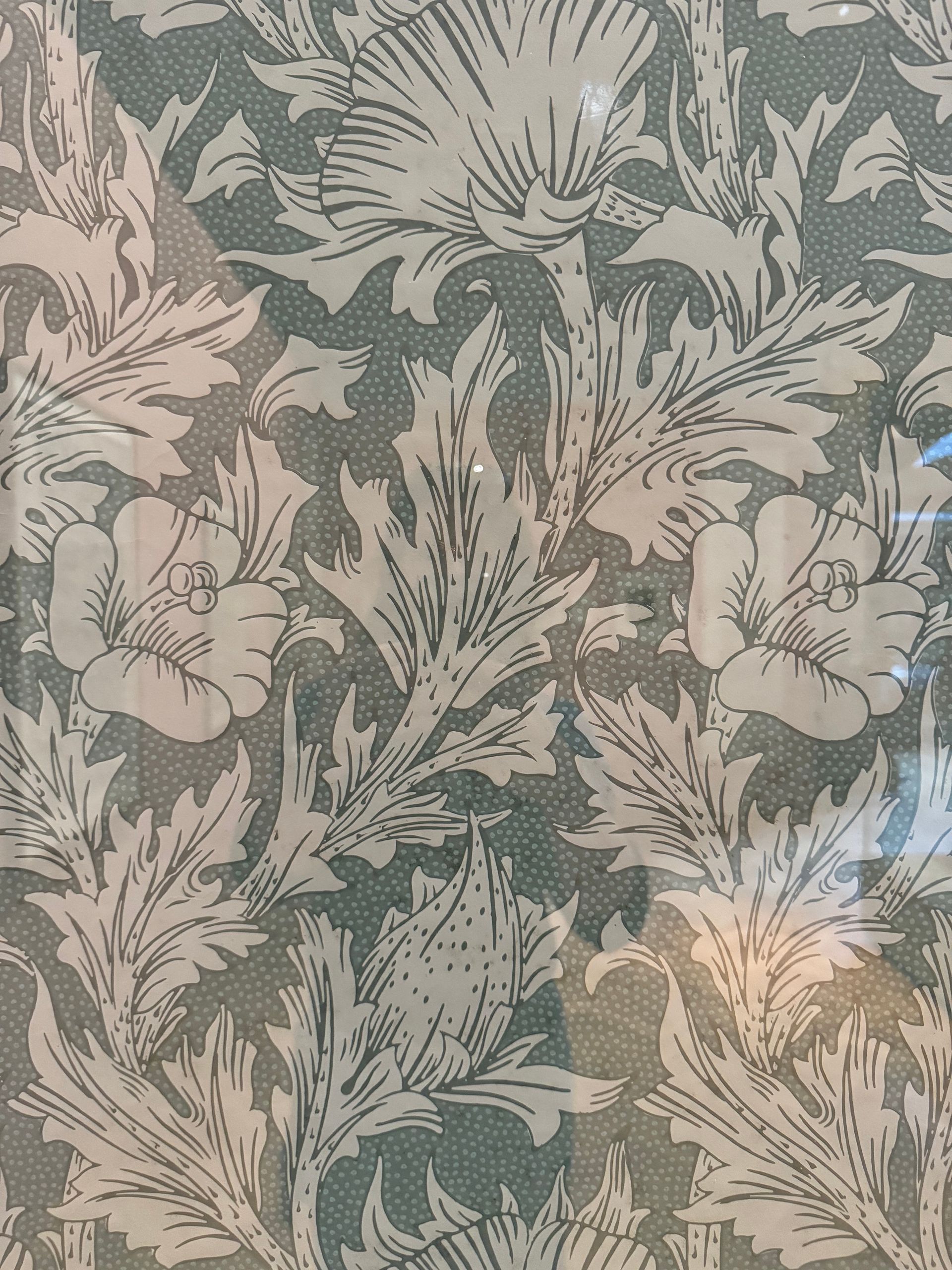

May's first wallpaper,

'Honeysuckle',

Button

Slide title

'Horn Poppy' was May's second wallpaper design

Button

Slide title

'Arcadia' was May's final wallpaper design before taking on management of Morris & Co.'s embroidery department.

Button

Slide title

This wallpaper is inspired by a set of embroidered panels depicting the seasons in stitch-work,

Button

Slide title

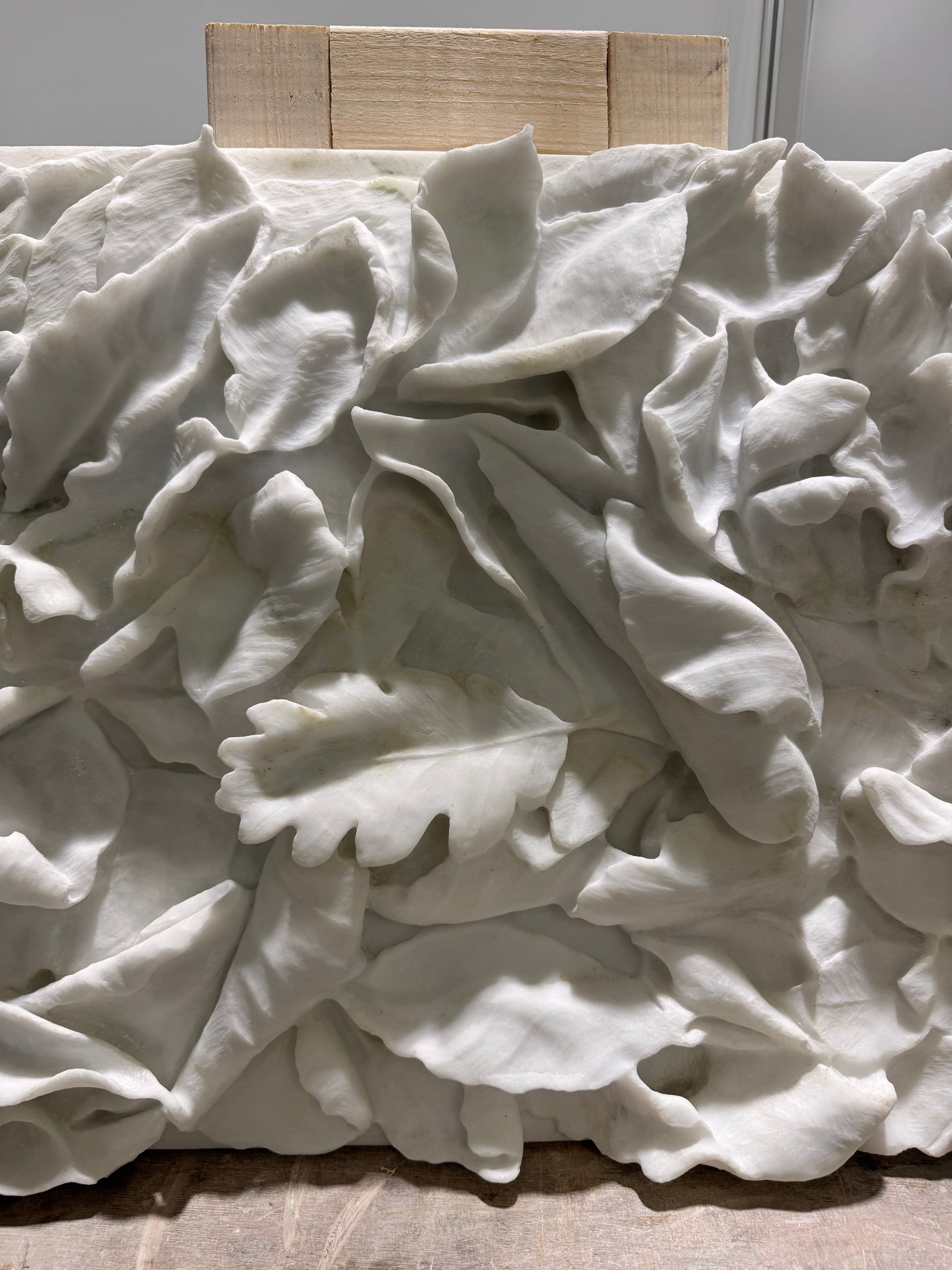

'Vine' Screen Panel Embroidery,

c. 1896. Designed by John Henry Dearle, embroidery overseen by May Morris

Button

Advocacy, Gender & Institutions

One of the most striking aspects of May’s legacy is her advocacy for women in design. The dominant guilds and art societies in Victorian and Edwardian Britain typically excluded women. The Art Workers’ Guild, for instance, did not admit women until the 1960s. Recognising this barrier, in 1907 May co-founded the Women’s Guild of Arts, together with Mary Elizabeth Turner, serving as its first president.

The Women’s Guild offered women artists, craftswomen, designers and makers an alternative professional network, opportunities for exhibitions, critique and mutual support. Its membership included names like Mary Annie Sloane (Honorary Secretary), Agnes Garrett and Mabel Esplin.

May also used her voice more broadly: in lectures, publications and correspondence she critiqued undervaluation of women’s handcraft, and argued for fair wages, respect for materials and technique, and the dignity of labour.

Legacy, Re-evaluation & Relevance Today

Sadly, despite all May had accomplished, her obituary in The Times initially described her as “daughter of William Morris, the poet”. Five sentences later it outlined her own achievements.

For homeowners of heritage properties, May’s story is so much more. Her design legacy is a reminder of the values that shaped the Arts & Crafts movement itself: authenticity, craftsmanship and a respect for the individuality of the home.

Just as she elevated embroidery beyond decoration into something meaningful and expressive, so too can today’s homeowners look beyond surface choices to create interiors that honour the spirit of their property.

Whether that means celebrating original features, commissioning bespoke craftsmanship or weaving personal stories into a scheme, May’s philosophy encourages us to see heritage homes not as static relics, but as living spaces enriched by artistry and care.

As an artist, May Morris is increasingly recognised not merely as William Morris’s daughter, but in her own right, as a designer, thinker, educator and feminist pioneer.

Her designs are sought after in museum collections and the art market. Her life offers timely lessons on authorship, the value of craft, gender equity in design and how women have always been makers, not merely muses.

For contemporary designers and heritage practitioners, May’s example reminds us that design is not just about objects, it’s about agency, voice, community and vision. In a world looking increasingly to balance technology, style and sustainability, the combination of craft, conscience and expressive design that she embodied feels more relevant than ever.

---

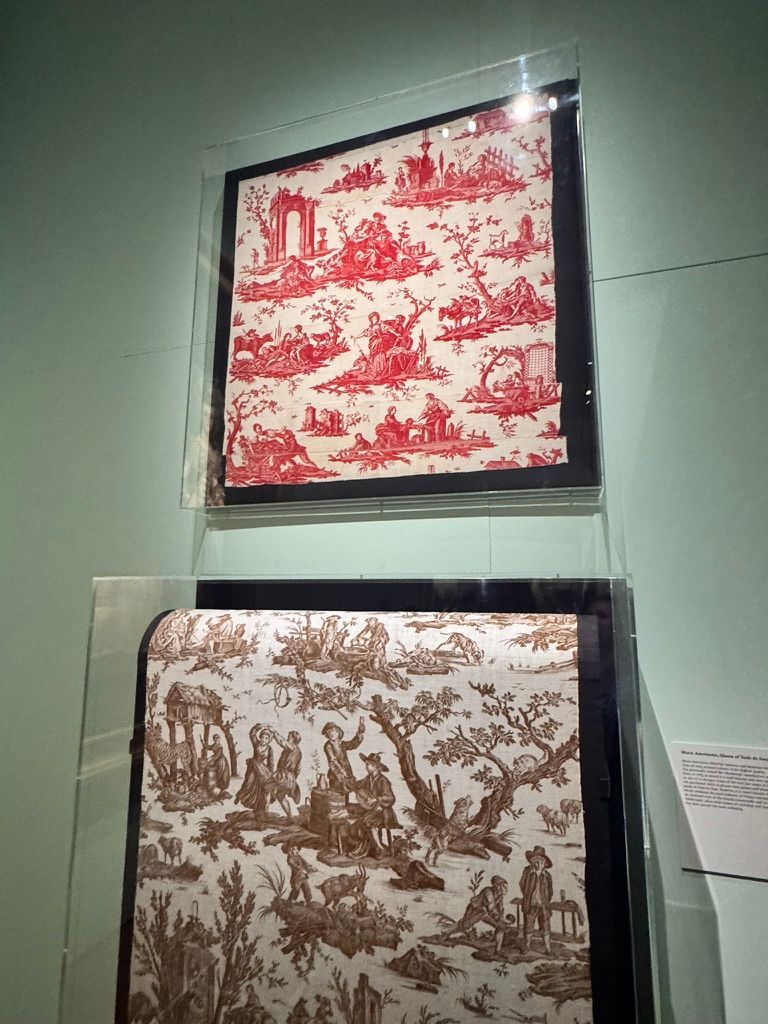

Photos: These images were taken at a temporary exhibition at the Russell-Cotes Museum, Bournemouth, on loan from the William Morris Society.