A historical tale: designing for the individual

Designing beyond aesthetics & functionality

The Case of Polesden Lacey

When creating a space, interior designers must go beyond aesthetics and functionality; they must also consider the subtle sociological factors that shape the lives and preferences of their clients.

Understanding these hidden elements can be a challenge, as noted by K. Izumi in 1968: “Identifying psychological and sociological design considerations is a difficult matter. So much is hidden behind our normal, but biased, level of perception.”

To explore this in more depth, let's look at Polesden Lacey, an Edwardian country manor in Surrey, as a case study.

A Modern House for its Time

Polesden Lacey was purchased in 1907 by Margaret Greville, a wealthy socialite from an industrial family. Built just a few years earlier, it was a modern marvel, boasting electric power, en-suite bathrooms, stables, and even a “motor house.” At the time, The Engineer magazine praised it as an example of how technology could meet the demands of comfort and hygiene in country homes.

With these functional needs met, Greville focused on using the space to fulfil her social ambitions.

Designing for Sociological Needs

Margaret Greville’s background reveals why understanding sociological factors is critical for designers. As the illegitimate daughter of a Scottish brewer, Greville inherited wealth from industry rather than aristocracy. She marrying into nobility, but to secure her place in high society she established herself as a prominent society hostess, an ambition that shaped every corner of Polesden Lacey.

An Entertainer’s Paradise

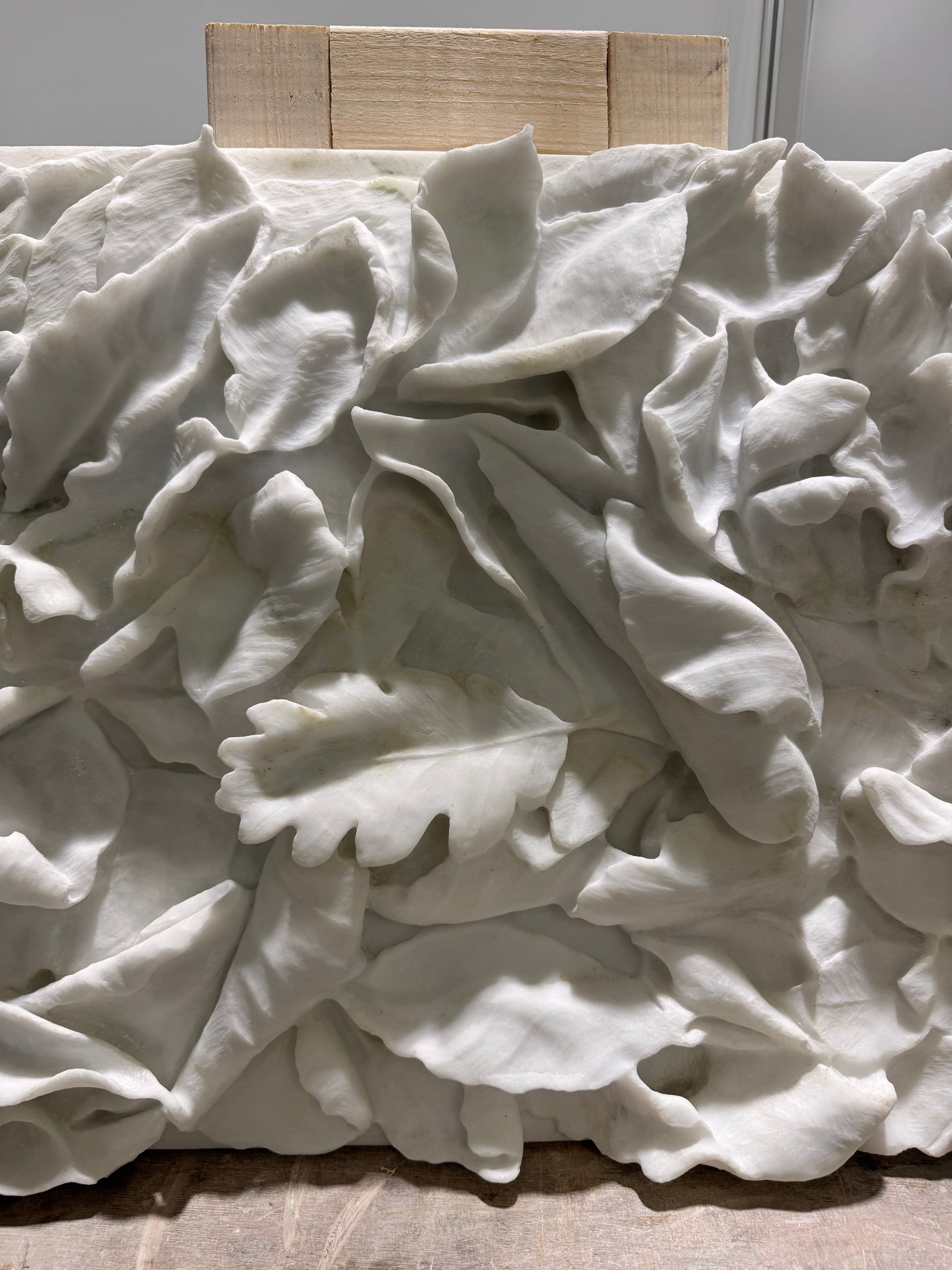

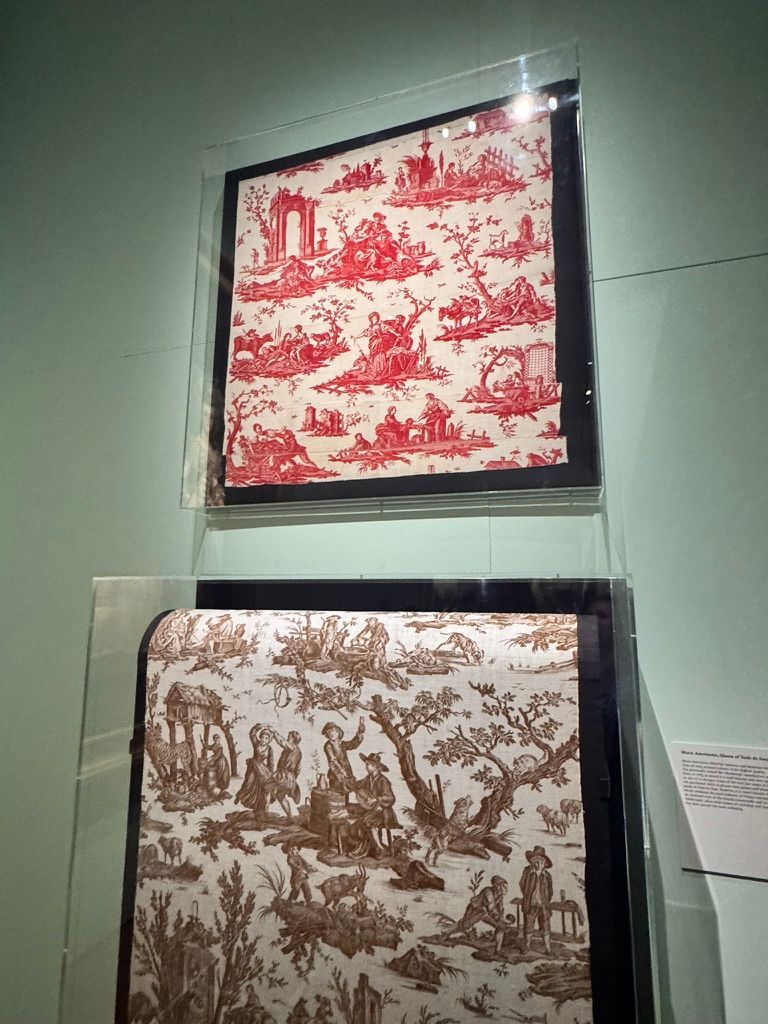

Greville commissioned the architects behind the Ritz hotels, Mewès and Davis, and the renowned interior design firm White Allom & Co., to transform Polesden Lacey into a sophisticated venue for entertaining. She filled the rooms with historical styles and architectural salvages, from gilded Italian panelling to a 17th-century carved church screen. These opulent settings hosted illustrious guests, including the Duke and Duchess of York (later King George VI and Queen Elizabeth), who spent part of their honeymoon at Polesden Lacey.

The design was not only about appearance; it served a purpose. According to the National Trust, Polesden Lacey became “synonymous with leisure, indulgence, and hospitality.” Greville’s guest list was equally influential, including political figures and dignitaries. It’s said that Harold Nicholson, MP, once remarked that Greville’s drawing room felt like the epicentre of foreign policy.

Practical and Personal Design Details

In her study, one detail highlights Greville’s specific needs. A window above the fireplace allowed her to see guests arriving up the drive while she sat by the fire, facilitated by a cleverly routed chimney flue that bends behind a false bookcase. At night, mirrored shutters would glide across to create an intimate atmosphere.

The interiors also accommodated Greville’s extensive collections, from paintings and silver to Fabergé carvings, with careful attention to lighting and window treatments to protect these treasures from sun damage.

A Testament to Design’s Impact

Polesden Lacey remains a testament to the importance of tailoring design to individual needs, both practical and sociological. The interiors reflect not only how Greville wanted to live and feel within her home but also the message she wished to convey to her guests. She bequeathed the property to the National Trust, ensuring that her legacy endures—along with the fascinating insights it provides into how design shapes both personal and social spaces.

For today’s designers, Polesden Lacey serves as a reminder: every element, from architectural salvages to the arrangement of windows, contributes to a client’s unique vision and lifestyle.